The Anthology of Balaji by Eric Jorgenson (4.2/5)

“Your network is your filter.” ~Don Tapscott. A simple idea, when taken seriously, can change the/your world.

Balaji’s simple idea is the Network State—a new way to organize people. Our current concept is the Country or its formal name, a Nation State. The Nation State came into existence about 300 years ago. Prior to that, people were aligned by empires, religious institutions, and roaming kin-based tribes w/ no defining borders.

Today, the internet allows people from different geographies to communicate instantly. And blockchains allow people to transact and maintain public records without a single person or institution in charge.

The Network State is a model of governance where people with shared values come together, pool money, buy land, develop it, make up with their own laws, and enforce them through code.

Would you rather have law enforced by humans or by code? Many people default to humans because they believe they can plead their case to an empathetic human being. But then you remember parole outcomes are decided by how hungry a judge is. Human judgment is prone to mistakes, as shown by this example:

But any Country or Network State has to solve the Gun-to-Head problem. Governments have a local monopoly on violence. What’s to prevent one from invading you? From confiscating your property, occupying your land, and seizing your citizens?

I think the root of freedom is the ability to inflict violence. Anyone can wave papers around and yell and scream say this/that but if somebody can come to your home, put a gun to your head, and deny your freedoms with impunity—then are you truly free?

Freedom comes in three ways: (1) Anonymity (= they can’t find you) (2) Militarization (= you make credible your own threat of violence) (3) Legitimacy (= be recognized by a country that respects sovereignty and has nuclear weapons).

There’s a clip in Game of Thrones where Littlefinger, one of the crown’s scheming advisors, says to Queen Cersei “Knowledge is power.” Cersei responds by ordering her guards to “Seize him. Cut his throat ... Stop. Wait, I’ve changed my mind. Let him go.

… Power is power.”

From First World to Third World by Lee Kuan Yuew (?/5)

What I find illuminating was Lee’s priority on safety when he became the leader of an independent Singapore in 1965. Singapore is a tiny piece of land, 50 kilometers across (equal to the length of one marathon) at its widest point on the 1st parallel north just above the equator. What’s to stop a hostile Malaysia from invading them?

In Lee’s words, his priorities by descending order of importance were: (1) get international recognition for Singapore’s independence, including membership in the United Nations (2) defend the piece of real estate (3) solve the economy as two of their immediate neighbors (Indonesia and Malaysia) had stopped exporting goods to them and were looking to bypass them as their trade middleman by dealing direct with other countries using their own ports.

1 and 2 were effectively security guarantees. This was in a pre-MAD (mutually assured destruction) world, in which armies could still fight to the end. Fortunately for Lee, the British Empire’s military retreat took ~6 years (1965-1971), long enough to give enough deterrence for Singapore to hire 18 Israeli military experts to train up a fighting force. To this day, Singapore, despite never having been in a war, has more military personnel than more populous countries, including the UK, Germany, Canada, and Australia.

It’s rare to see a book about the leader of a country without a hardcore political agenda attached to it. Even rarer to get it in his/her own words. It’s refreshing, and Lee’s characteristics shine through in his prose. Wise, prudent, strong, and clear. I just started it though so can’t give a rating yet.

White Mirror by Tinkered Thinking (3.9/5)

If Black Mirror is the devil, then White Mirror is the angel. 31 pseudo optimistic anti-dystopian short stories. Reminds me of David Eagleman’s 40 Tales from the Afterlives.

The Portrait of a Mirror by Natalia Joukovsky (4.3/5)

Pretentious prose about pretentious people doubling down on all things pretentious. Prose that is both ridiculous and magnificent1. Whole chapters written as emails. The author isn’t afraid to recursively, recursively, recursively experiment.

The plot follows two privileged and wealthy couples in late 20s/early 30s in New York City, who, unbeknownst to them, swap partners and ride the associated roller coaster of emotions. Is this work the cultural relic of an East Coast upper-class era of the 2020s, reminiscent of the Great Gatsby for the 1920s?

It’s written in a way I prefer to savor rather than devour.

All of Chase Hughes’ Work (6 Minute X-Ray, Behavior Ops, Ellipsis Manual, Phrase 7) (4.2/5)

When I read non-fiction, I like to figure out the context and motivation which it was written. For 20 years, Chase Hughes’ job was to train military operatives to walk into a Russian bar, and within the span of one interaction, convince him to spy for his rival country.

That’s a green flag because there are downsides if he gets it wrong. Chase has skin in the game. We talk a lot about “soft skills” that sound great in theory but aren’t grounded in reality.

Here’s one counterintuitive human truth I learned from Chase. To get a bad guy to confess to a crime, or a partner to confess to cheating, or a child to stealing— don’t go in guns-blazing, Hollywood style, tough-guy accusatory attitude.

No, instead (1) first socialize: Many people cheat, it’s normal, you’re not the only one (2) then rationalize: what you did makes total sense, it’s logical, your needs probably weren’t met (3) then minimize: it’s not a big deal, no really it’s not, but I do need to know what happened for my own sake (4) lastly project: it’s not your fault, you were just following orders, or maybe a friend told you to do it.

Some of his stuff leans speculative, like on MK Ultra and the Manchurian Candidate, but others, like on blink rate, is solid.

The way I’d critique Chase is the same way I’d critique coders who say “everyone and their mom should learn how to code” or salespeople who believe “everything, including when walking down the street or talking to your kids, is a negotiation” or readers who say “everyone should go read a book” or “those people” who say “life is all about relationships.”

So Chase isn’t immune to our tendency to over-state the importance of our field. For him that means over-explaining events through the lens of human behavior. Chase has a fetish for Jason Bourne esque movies so he paints a dark-themed classified-CIA aesthetic across his work, which I personally appreciate. True to military style, he tends to rely on 3, 4, 5, and 6 letter acronyms. But compared to other authors on these topics, his work has relatively low ideological bias.

The Beginning of Infinity by David Deutsch (4.6/5)

Deutsch theorized the many-worlds interpretation of quantum mechanics. The idea that there are multiple copies of us living in multiple worlds. As unintuitive as this sounds, Deutsch reminds us that there’s nothing “intuitive” about the Theory of Relativity. It was Einstein who suggested—not only are we being pulled down toward the Earth’s center—he called this ‘gravity’—but we are also pulling the Earth up towards us!

I found the second half of Chapter 13 insightful, where he says 75% of the effort in decision-making is in coming up with the options; the last 25% is deciding between them. Deutsch didn’t use these numbers per se, but he points out that the final selection process, which we seem to obsess about, is the most trivial. In his words:

“It is a mistake to conceive of choice and decision-making as a process of selecting from existing options according to a fixed formula. That omits the most important element of decision-making, namely the creation of new options.”

Ultimately, this difference is what separates AI from AGI. Any AI can maximize a utility function, via reinforcement learning or any of the other methods, but can an AI change its utility function? Can it change what it optimizes for? Can it do something it’s not programmed to do?

The End of Eternity by Isaac Asimov (3.9/5)

It’s where Deutsch stole the name from. The Beginning of Infinity is the antonym of End of Eternity.

This story is about a group of time travelers who make continual edits to 70,000 centuries of human history to ensure stability for trillions of citizens. What they don’t realize is their corrective edits come at the cost human civilization not reaching its full potential.

It’s one of those books where good guys turn out to be the bad guys on the very last page. Such a plot twist must’ve been hard to pull off, hence why Asimov is the GOAT of science fiction!

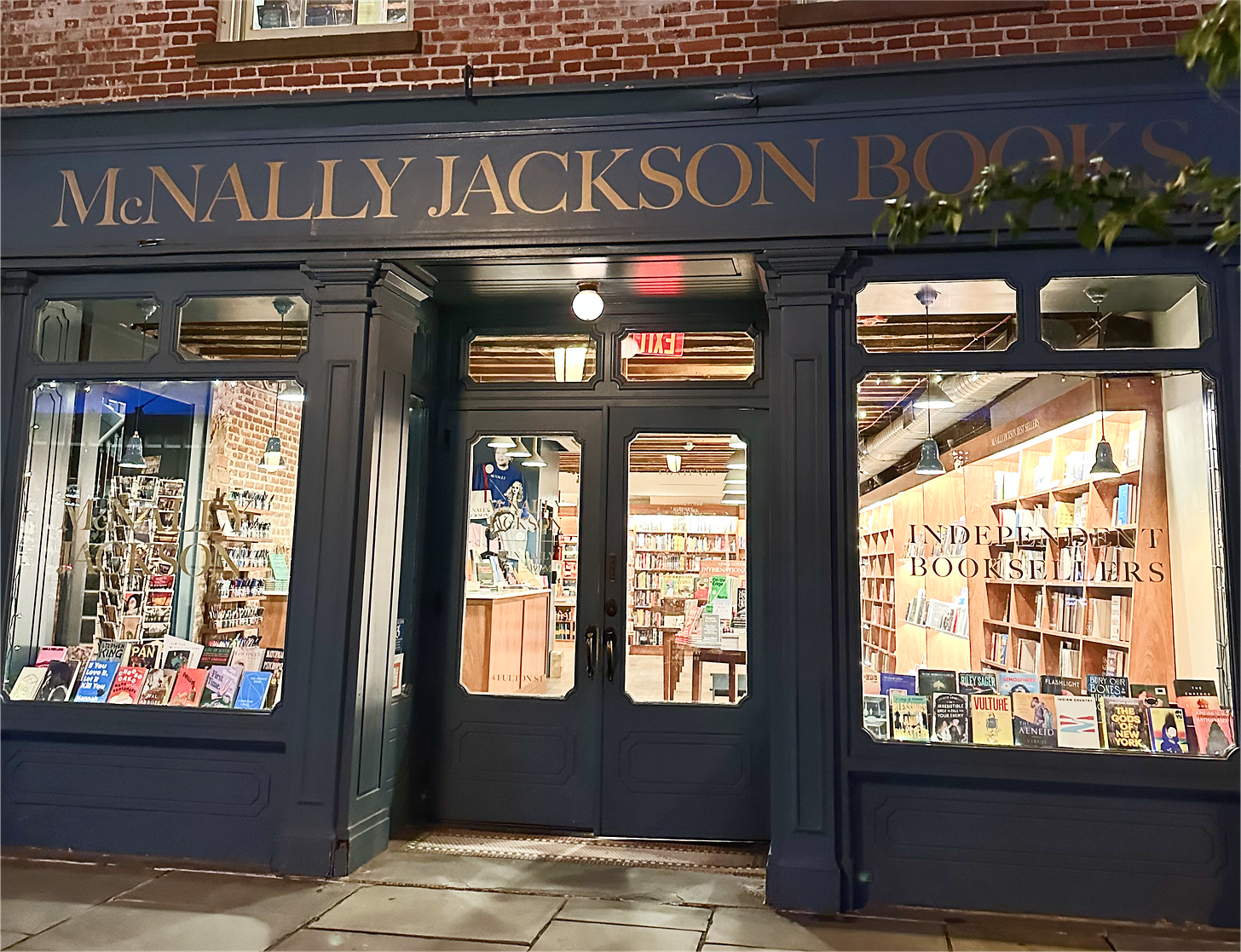

The Capitalist Manifesto by Johan Norberg (2.7/5)

Some time ago, I had walked into the McNally Jackson bookstore in FiDi on a friends’ recommendation and found myself in a serendipitous debate with a communist (yes, a self-proclaimed communist, in nyc, in 2025). Though it wasn’t a debate insofar as me asking him repeatedly what he meant by “owning the means of production”. The gentleman had taught music, so I asked “Did you feel exploited by your employers?” “No, they were actually very nice.” Like many theories, Marxism is one that sounds way better on paper than in practice. “From each according to his ability, to each according to his needs.” A world of perfect efficiency. How cool is that?

But I wanted to find a good basis for capitalism (the primary alternative economic ideology), which led me to The Capitalist Manifesto. But this wasn’t it. In Chapter 6, the author trashes on Italian economist Mariana Mazzucato. Do you know when philosophers critique other philosophers? You need a level of knowledge and sophistication just to understand why he’s so mad in the first place.

There was a good anecdote, which I’ll copy in the footnotes.2 But overall hard to read and cumbersome to verify. I may give it a second shot in the future.

Ballerina by Patrick Modiano (2.3/5)

Classical ballet has been a longstanding curiosity of mine, and I was delighted to finally find a book about the subject at the Rizzoli designer bookstore on Broadway. But instead of learning about the Balanchine world, I was left empty-handed and empty-hearted. Maybe my expectations were too high? Maybe the translation fell flat? Auteur français Patrick Modiano won the Nobel Prize of Literature in 2014. While the first 1/3 was decent, the prose reads like an inferior Murakami.

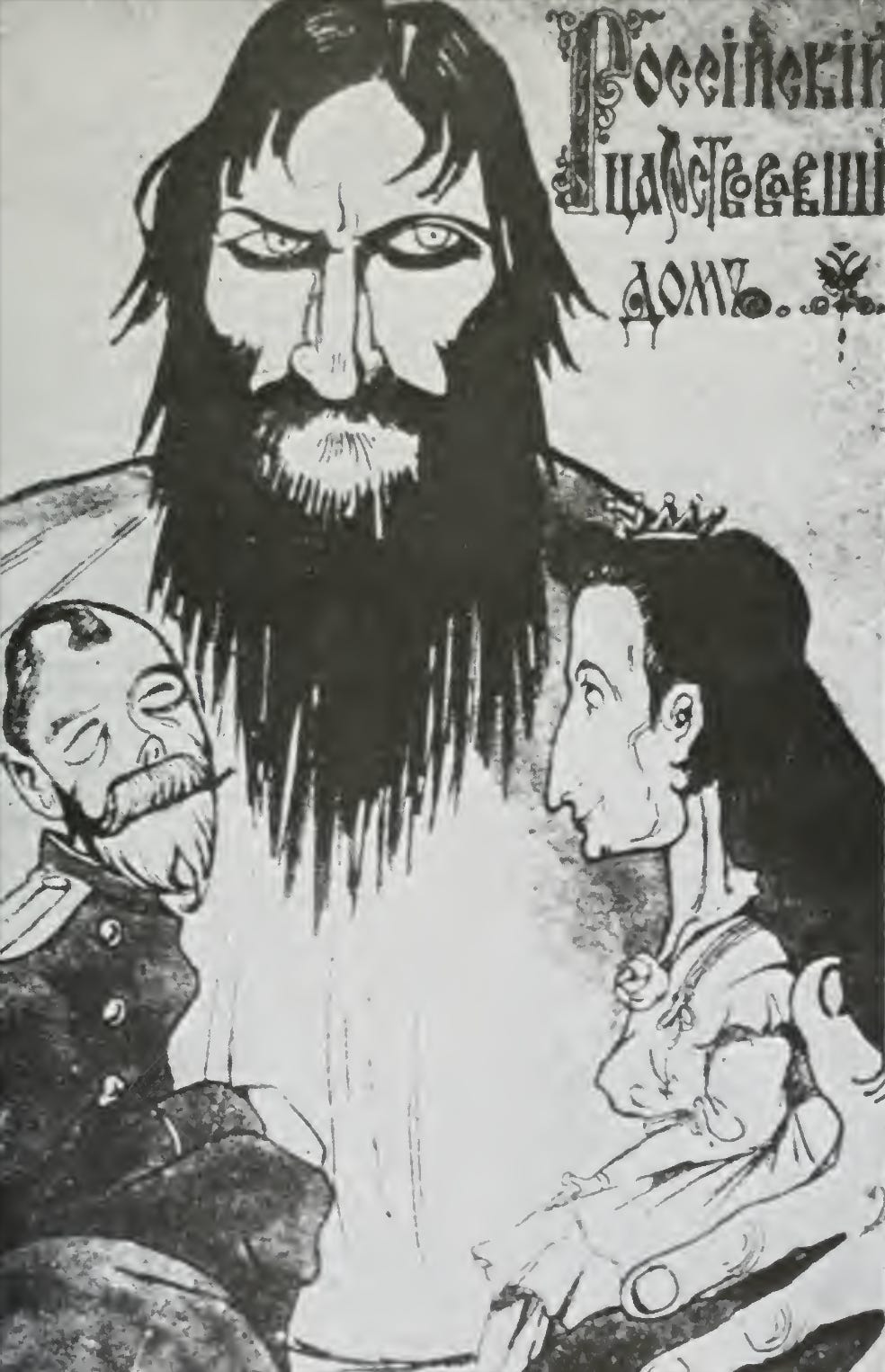

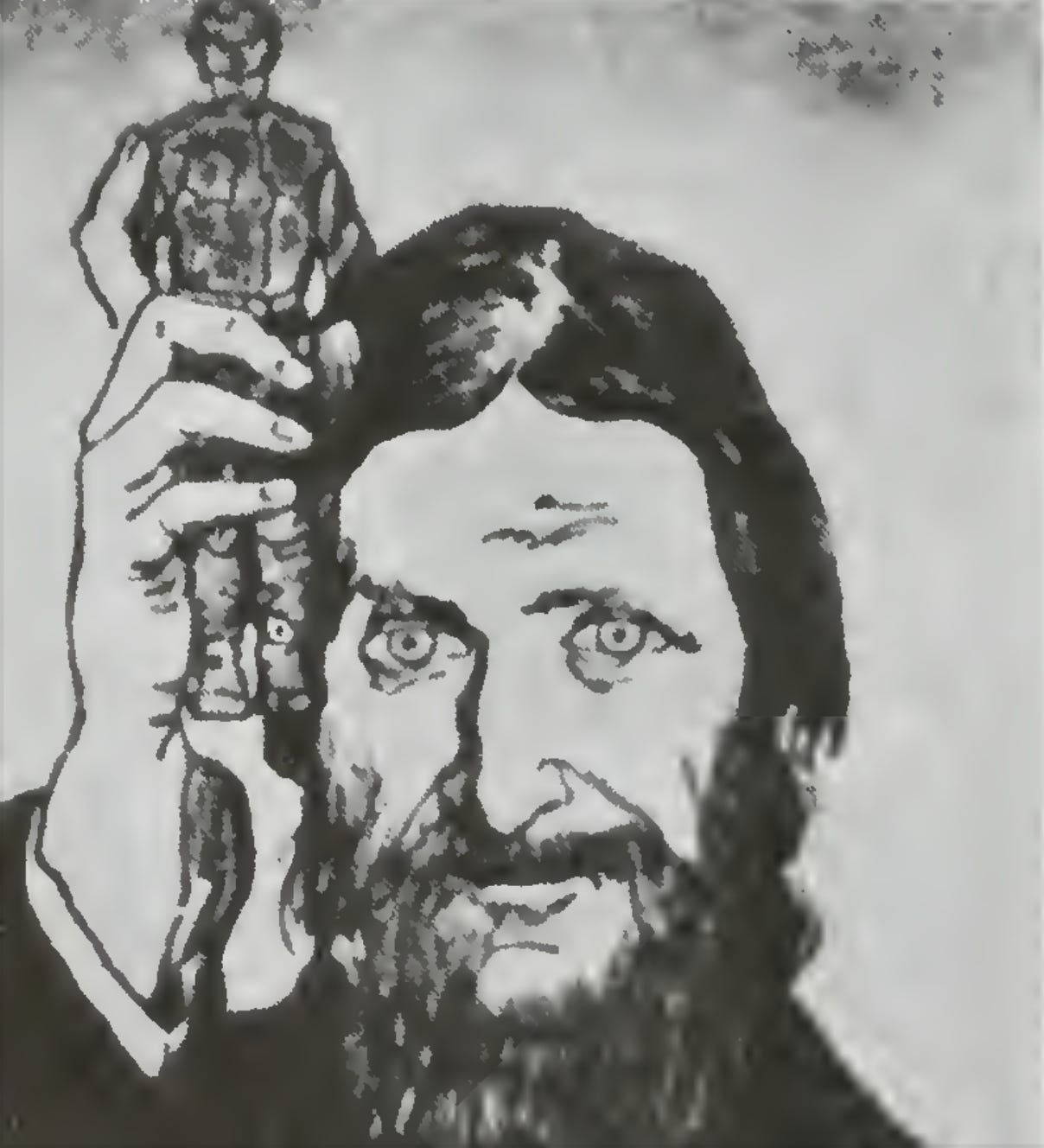

Story of Rasputin by Jay Robert Nash (4.8/5)

Yeah, Jeffrey Epstein probably slept with a few underage girls, but Grigori Rasputin slept with the entire Russian nobility—and almost got away with it. You can’t read Rasputin’s story without having multiple “no way you’re serious and this actually happened” moments. Truth, indeed, is stranger than fiction.

This is the last book review. Give it a read. It’s supremely fascinating. I’ve attached the entire biography below. 👇

Grigori Efimovich RASPUTIN

Mystic (1872-1916)

The "Mad Monk of Russia" was born Grigori Efimovich Novyky in the Siberian town of Pokrovskoye some time in 1872. He grew to be a strapping peasant with hypnotic powers and a sexual charisma that no Russian noblewoman, if certain accounts are to be believed, could resist once he had ingratiated himself to the Imperial Family. As a young man Rasputin joined a heretical sect called the Khlysty, a sect of flagellants who not only beat themselves bloody each night for sins real or imagined, but, as part of their pagan rites, partook of all-night orgies in which couples interchanged sexually at random. Leading the beatings, wild, naked dances, and taking on more sex partners each night than any other member of the sect, was Rasputin, whose stamina and sexual appetite qualified him as one of the world's foremost satyrs. His very name, given to him by fellow members, signified his sexual prowess in that it meant "debauchee." Rasputin, at the time, was married and had young children, but he nevertheless led the Khlysty cultists in their wild revels each night, forcing his wife to join in the orgies, foisting her naked upon other male members while he sought out the prettiest of the females present. While ploughing a field one day, Rasputin later claimed, he had a blinding vision of the Virgin Mary and she instructed him to go throughout the land preaching his brand of sexual religion. In truth, Rasputin fled his home town, abandoning his wife and three children because he was under investigation by the local police and orthodox priests outraged at the conduct of the Khlysty. For several years Rasputin traveled nomadically through Russia, calling himself a starets, a self-appointed holy man who claimed to heal the sick and one who practiced the strangest type of baptism known to any religion. Rasputin would enter a town and call a meeting of the ignorant, illiterate peasants, making sure the local priest was absent from the community at the time. He would then proceed to baptize the entire village in his own inimitable fashion, leading the naive populace to the river where he would quickly baptize the males, children and older females. He would then announce that to make the young women "clean of spirit," they would have to undergo the pleasures of the flesh with a holy man, namely himself. The innocent peasant males, fathers, brothers, and husbands, would stand idly by at these times and watch as their young women—Rasputin was careful to select the prettiest for his sexual blessings—joined the monk in the public baths or river and under his coitional rituals. The spreading of Rasputin's sexual religion produced countless children strewn, all direct offspring of the monk, from western Siberia to European Russia. On occasions, he would return home to describe in detail his experiences. His blue-eyed wife, Praskovia, submitted completely to Rasputin's lifestyle, believing that his promiscuity was divined by God. Even his daughter, Maria, came to believe that her father's satyrism was heavensent and she later wrote a book glorifying his every act, including his wholesale orgies with dozens of women, detailing these exploits as high religious rites.

Wrote Maria: "His female devotees. . . were drawn to the worship of his phallus, endowing it with mystical qualities as well as sexual ones, for it was an extraordinary member indeed, measuring a good 13 inches when fully erect ... As their passions were aroused, there was a tendency to forget the ritualistic aspect. . . and the participants would fall into a general orgy." Thousands of Russian peasants came to sing the praises of "Father Gregori, our savior," and his reputation spread across the land to St. Petersburg, to which Rasputin traveled in 1903. At the time he was fleeing police in several cities and towns who intended to arrest him at the request of the Russian Orthodox Church, which had condemned him as a heretic; the Khlysty had already been wiped out by this time, its members disbanded. Fortunately for the mad monk, the flighty and idle noblewomen of St. Petersburg thought him a novelty and invited him into their homes so that he could lecture them on spiritual matters. The first grand palace Rasputin entered was that of the Countess Ignatiev, who was close to the Empress. It was later reported that Rasputin raped the countess and several other noblewomen who attended that first meeting, along with several female servants. The women later gossiped that they had "undergone sexual salvation" at Rasputin's hands. Moreover, they had been hypnotized, they said, by this incredible mystic. The man who entered high Russian society in 1903 was anything but physically attractive. His best biographer, Rene Fulop-Miller, described the monk at this time as "ungainly. . . coarse. . . and ugly. . . His big head was covered with unkempt brown hair, carelessly parted in the middle and flowing in long strands over his neck. On his high forehead a dark patch was visible, the scar of a wound. His broad, pock-marked nose stood out from his face, and his thin pale lips were hidden by a limp, untidy mustache. His weatherbeaten, sunburned skin was wrinkled and seamed in deep folds, his eyes were hidden under his projecting eyebrows, the right eye disfigured by a yellow blotch. The whole face was overgrown by a dishevelled light brown beard." Rasputin's body stench was overpowering. He ate with his hands and his beard was matted with food that rotted in the hairs for weeks on end. He would sometimes go for months without washing his hands or face, claiming that taking baths was hedonistic, the devil's work, that humans must smell like the animals of the woods to keep their "natural order of the flesh," whatever that meant. Rasputin's terrible body odor, however, did not diminish the numbers of high born Russian females who flocked to his filthy apartment to undergo his "baptism of the flesh." In fact, his bizarre behavior only served to whet their appetites. When invited to the grand palaces of the nobles, Rasputin always excused himself from the large halls, preferring small rooms where he could gather the females about him. He would then go into a wild dance, gazing intensely at those women he wished "to baptize." They were mesmerized rank upon rank and fell prey to his lustful grabs and caresses. "Soon a wide circle of women from all classes of society," reported a biographer, "ranging from ladies of the highest rank down to servant maids, peasant women, and seamstresses, looked on Rasputin as a higher, divine being." The Empress Alexandra first heard of Rasputin's name from a mystic named Feofan, an ordained priest who had tried, at the Empress' request, to aid her hemophiliac son, Alexis, only heir to the Romanoff throne. Alexis suffered painful and seemingly unstoppable hemorrhaging at the slightest fall. If he merely brushed a sharp-edged table he would begin to bleed. The Empress had tried every known remedy, and had consulted with hundreds of specialists. Nothing seemed to help her son's condition. In desperation she turned to mysticism, consulting many wandering religious zealots. None were able to stop her son's bleeding. Father Feofan also tried to help the boy but failed. He was sent away, but before he departed the Royal Palace at Tsarkoe Selo, outside St. Petersburg, Feofan mentioned Rasputin's name, saying that he was reported to be the greatest healer in Russia. When Alexandra consulted with Countess Ignatiev, she was told that, indeed, the starets was a worker of miracles. She herself had witnessed marvelous healings in her own home, the countess exclaimed, performed by none other than this very Rasputin. The countess neglected to mention the orgies she and her noble-born sisters had joined in with the wild-looking monk. Rasputin was sent for, arriving at the Royal Palace in November 1905. On the night of his first visit, Rasputin took pains to bathe and wash his face. He wore a clean black robe called a caftan. He said nothing as he was led toward the Czar's study. At the study door he suddenly turned and glared at his guide, a noble-born woman, and snarled: "What are you gaping at?" He then spun about, putting on his best face, the one with the wide and pleasant smile, and rushed into the study where the Czar and his consort waited to greet him. Instead of kissing their hands, as was the custom, Rasputin boldly walked up to the royal couple and kissed them paternally on the forehead.

Ironically, it was only a matter of minutes before attendants came rushing from the nursery to report that Alexis had had another accident and was bleeding. Frantic, the Empress begged Rasputin to do what he could for the child. "Certainly, certainly," the monk replied and was led to the nursery. Entering Alexis' room, Rasputin fell to his knees in a dark corner. He prayed incoherently as the royal couple fidgeted, listening to their son moan in agony in his bed at the far side of the room. Rasputin was suddenly on his feet, moving quickly about the room, blowing out all the candles except one which he held in his hand, carrying it to the foot of the boy's bed. He held the candle to his own face, close to his eyes and made the sign of the cross as the boy stared at him. Rasputin undoubtedly hypnotized Alexis, and, while he was in a trance, sat on his bed, introducing himself as "your friend, the best friend you have in this world." He began to gently caress the child's arms and legs, including an area that was bleeding, saying all the while: "Now, don't be afraid, Alesha, everything is all right again... Look, Alesha, look, I have driven all your horrid pains away." He continued his massage, stroking the boy from head to foot. "Nothing will hurt you anymore, and tomorrow you will be well again. Then you will see what jolly games we will have together!" The bleeding stopped. Rasputin had performed his miracle. Alexis grew completely dependent upon Rasputin in the months and years to follow, listening spellbound to the monk's wild stories of life in Siberia. Whenever the heir to the throne began to bleed Rasputin was called, and he soon hypnotized the impressionable child to the point where he could actually control the hemorrhaging. For this inestimable service Rasputin was, at first, allowed the freedom of the palace and given any amount of money he desired. But it was power Rasputin wanted and he got it. Nicholas II and Alexandra became his willing pawns as he proved to be the only one who could keep their son alive. When he entered the palace it was the royal couple who gratefully kissed his hand. Gradually, insidiously, as was his style, Rasputin worked his way into affairs of state, first making suggestions, then demanding that the Czar do his bidding. He was generally obeyed. Whenever the Czar proved critical of Rasputin, the monk would simply blackmail him into submission. Following one of these confrontations, the monk returned to his luxuriously appointed office-apartment to laughingly boast of his conquest to his assembled harem. "Well, I went straight in," he bragged. "I saw at once that Mama [the Empress] was angry and defiant, while Papa [Nicholas] was striding up and down the room whistling. But, after I had bullied them both a little, they soon saw reason! I had only to threaten that I would go back to Siberia and abandon them and their child to disaster, and they immediately gave in to me in everything." He held up his fist and said: "Between these fingers I hold the Russian Empire!" The office-apartment where Rasputin lived was guarded night and day by Imperial cossack troops, lest someone attempt to injure the monk; he had received many threats against his life after he became what he termed "the czar above the czar." He dispensed political favors to any and all, but for great fees; all paid in gold at his insistence. Some of his fees for obtaining appointments through the Czar—bestowing estates, granting franchises were not for cash. He traded in flesh. If he knew that a certain nobleman or merchant had a particularly good-looking daughter or wife, he would demand that these women be sent to him for "spiritual guidance." Incredible as it seemed, most males seeking his favors through the throne readily agreed, escorting their women to the mad monk's apartments and waiting until he had finished his assignations with them. Sometimes there was a waiting line of several dozen women, sitting patiently in Rasputin's outer chambers, preparing themselves to partake of sex with the starets. Often as not, Rasputin would call a half-dozen women in at a time, ordering them to disrobe immediately—"sinners ashamed of their bodies wear clothing"—and then join him in a room that was really one large bed. The female visitors had heard of the monk's overwhelming body odor by this time and took the precaution of literally bathing in perfume so that their scents would overpower his. Said Prince Felix Yusupov, who hated Rasputin and was the eventual ringleader in a successful conspiracy to murder the monk: "His office smelled like that of a French whorehouse, so thick was it with the scent of perfume. No wonder! He had made of our women whores, low and disgusting creatures, tainted by his awful disease." The last remark referred to Rasputin's having permanent gonorrhoea after his nonstop sexual liaisons, or worse, syphilis, a disease many claimed that had made him insane. The Russian secret police assigned an around-the-clock surveillance on Rasputin and his every guest was noted, including their gifts to the monk, from gold to the number of wine bottles and tins of caviar they carted into his apartments in huge baskets. Rasputin was followed everywhere. Agents watched as he was driven to the estate of Madame Karavia where he frolicked with the women of the house, got drunk, then ran outside and leaped upon a horse, stark naked, and raced about the palace, drinking wine from a bottle. Rasputin went to the train station one night and entered the compartment of a departing countess, agents noted, having the train wait until he had ravished her repeatedly.

The police reports on Rasputin's nocturnal activities, which amounted to huge volumes after several years, were revealing, to say the least. Here are but a few: "On the night of 17th to 18th January Maria Gill, the wife of a Captain in the 145th Regiment, slept at Rasputin's." "26th January. This evening a ball took place at Rasputin's in honor of some persons who had been released from prison, at which behavior was very indecorous. The guests sang and danced till morning." "16th March. About 1 a.m. eight men and women called on Rasputin and stayed till three. The whole company sang and danced: when they were all drunk, they left the house accompanied by Rasputin." "3rd April. About 1 a.m. Rasputin brought an unknown woman back to the house; she spent the night with him." "11th May. Rasputin brought a prostitute back to the flat and locked her in his rooms; the servants, however, afterward let her out." "On the night of 25th to 26th November Varvarova, the actress, slept at Rasputin's." On one blustering cold February night, police noted that more than forty women, from 8 p.m. to dawn, visited the monk, some staying no more than fifteen minutes. They were the wives of diplomats and generals, noblewomen, actresses, street whores, maids and even a cook from the Royal Palace. The monk slept with them all, according to the police report, and all left his apartments in happy moods. Even the Empress, accompanied by her four daughters, visited the monk at his office-apartments, but on these occasions Rasputin was on his good behavior. These visits, however, prompted the leading religious zealot of the day, Iliodor, to denounce Rasputin, a man he had originally sponsored during Rasputin's first visits to St. Petersburg, defending the starets against the accusations of orthodox church leaders. Iliodor obtained the police reports of Rasputin's scandalous behavior and published a reviling pamphlet entitled "The Holy Devil," in which he detailed the monk's intolerable transgressions, labeling Rasputin as "the curse" on the throne of Russia. Further, Iliodor blatantly stated that Rasputin and the Empress were having constant illicit sex, and that Rasputin was undoubtedly enjoying the sexual favors of the four Grand Duchesses. For this libel, Iliodor was banished. Rasputin saw to that. Like Joseph Balsamo, the notorious Cagliostro who once said "I can afflict as well as heal." Rasputin would tolerate no interference with his private or public policies. If a man did not turn over his wife or daughter to him, he was criticized by the monk to the Czar and his fortunes fell. If a diplomat or general took issue with Rasputin, the monk would hold a conference with the Czar, instructing him to either imprison or banish the offending person, and this was almost always done.

Enemies of the mad monk began to increase in number. First, reports of the monk's behavior—actual rapes of high-born women—were registered with the police. The police threw away these reports or ignored them. Next, members of the court went to the Empress and even Nicholas with stories of Rasputin's excesses, but the royal couple refused to believe the tales. Their beloved "friend" was a saint, they insisted, maligned and slandered because of his divine mission on earth and because he "had the ear of God." Opponents concluded that more direct action was necessary and assassination began to be plotted in early 1913. The conspirators, however, talked too much and the plot was overheard by one of Rasputin's spies, Sinitsin by name, who warned the monk. The plotters were arrested and jailed. Iliodor and others then formed a "Committee of Action," and decided that the instrument of their wrath would be a demented creature, Kionia Guseva, a morbidly neurotic prostitute who was dying of syphilis. She was easily persuaded to right Rasputin's "vicious deeds" by murdering the monk. To that end, she waited outside the monk's quarters. On June 28, 1914, Rasputin appeared in the street to collect a letter from the Empress. Kionia Guseva ran forward to the starets, begging for alms. As the monk reached into his robe for his purse, the prostitute produced a long knife and plunged it to the hilt into Rasputin's abdomen. As he fell forward, Guseva screamed: "I have killed the anti-Christ!" She ran shrieking down the street. Rasputin steadied himself placing his hand tightly over the bloody wound, staggering into his apartments. A doctor was called and an operation was performed as Rasputin lay on his dining room table. He was saved. The would-be assassin, Guseva, was put into an asylum for life. While Rasputin recovered, Czar Nicholas led his country into World War I, an act the monk later claimed he would have prevented had he not been hospitalized. Several more plots against Rasputin's life were still-born over the next two years as Russia bled to death in the trenches of the Eastern Front. Rasputin had then little control of the Czar, who was invariably close to the front directing his troops. The mad monk went on directing policy in Russia during the Czar's absence, having a complete hold upon the Empress through his hypnotic care of Alexis. Prince Felix Yusupov, however, vowed that he would kill the monk and rid his country of "a vile cancer" or perish in the attempt. He and a close-knit group of nobles inveigled Rasputin to his palace on the night of December 29, 1916. As bait the prince used his beautiful wife, Irene, whom he knew the monk coveted greatly. Rasputin arrived drunk and was shown to an empty banquet hall. Yusupov told him that he was late, that the guests had already eaten and departed. "I don't care about the guests," Rasputin said. "Where is your wife?" Yusupov told the monk that she would join him shortly, and offered him some cakes and wine, both of which were laced with enough poison to kill a regiment. Rasputin ate an entire tray full of cakes and drank three bottles of the wine while the prince sat in shock. Yusupov finally got tired of waiting for the cyanide to kill his "superhuman monster" and suddenly rushed Rasputin, driving a dagger into him a dozen times until the monk fell to the floor bleeding from his wounds. The prince summoned his co-conspirators and they tied the monk in ropes. Suddenly Rasputin jumped up, breaking his bonds and lurching toward the petrified prince. Yusupov managed to draw his pistol and he emptied this into Rasputin as the monk lunged for him. Finally stilled, the monk was tied with chains and then dragged to the Neva River. The conspirators cut a hole in the ice and dumped the monk's body into it. Two days later Rasputin's bloated body was found on the river bank. He had somehow survived the poison, the stabbings and the bullets. He had almost survived the frozen waters of the river, but his incredible strength had finally given out just as he managed to punch a hole in the ice and surface. His lungs were filled with water and he was officially listed as having drowned.

Great numbers of Russians, peasants and high-born alike, mourned Rasputin's death. The Empress went into shock. Yusupov and his wife left the country before they could be arrested. (They settled down in New York, the prince dying in 1967.)

A large chapel was built on the royal estate outside of St. Petersburg and into this went Rasputin's body. However, the Romanoffs were toppled two years later and executed, and the monk's chapel was destroyed by revolutionaries. His remains were dragged from his casket and soaked in kerosene, then burned.PRETENTIOUS PROSE

“Witnessing her charm someone else was far more punishing than universal gloom or petulance. There was something chastely perfidious about it—the relative demeanor differential, its wide expanse—like she was systematically excluding Wes from the essence of her winning Diana-ness he most wanted to singly trounce and possess.”

“Back when he was putting together applications to MFA programs as a college senior, Dale had mustered enough self-awareness and insight into the modus operandi of graduate school admissions not to submit some story about himself, to write instead about the abduction of an underprivileged woman in South Boston that demonstrated all of the appropriate intersectional sensibilities.

He’d genuinely believed in the outraged moralism of his own story, of course, but he also had to admit he’d only written it to satisfy the canon-balancing bloodlust of a few purple-pen-wielding deans.”

CAPITALISM VS COMMUNISM

In The Son of a Servant, Strindberg tells the story of the worker who comes to a poor village and who has an idea.

He borrows money, buys raw materials and tools and asks peasant girls if they can help him weave straw and peasant boys if they can sew straw hats, and suddenly a new business is operational.

He pays the workers as agreed, never misses a payment on his loans and pays for the raw materials and still manages to make a small profit. That profit incentivizes him to develop more efficient production, create better designs, find larger markets and constantly stay one step ahead of the competition.

Business is getting better and better and suddenly the village is flourishing. The workers are also better off, the hungry are fed, and the worker – who is now a capitalist – is rich.

But one day a spoiled young socialist summer worker comes to the village and incites the workers: ‘this capitalist has become rich off your work’, he is ‘a thief’. He ignores the fact that their work had always been there, and it was only this new business model that made their work productive and valuable to consumers.

The young socialist succeeds in convincing the workers to take the hat manufacturer’s money and his machines. Now, no one is paying them unless they sell something, and no one is constantly on the lookout for the best raw materials, repairing the machines, streamlining production or looking for new markets.

The villagers continue to work, but find that the profits and the salaries soon disappear. And no worker ever came up with the crazy idea of risking their savings to start a factory in the small village again – a village that soon fell back into poverty and hunger.

Quite a diverse set of books as befits a world traveler like you! Have you reverted back from Zaffre?

Love the selection - been meaning to read many of them. Like Network State and LKY's book!